By their very name, fairy tales seem to be something apart—stories that happen in a place of other, that promise happy endings to even the most hopeless situations. And yet, the great fairy tales, even in their most sanitized versions, have always told of humanity’s worst traits: inequality, deceit, ambition, jealousy, abuse, and murder. And the great fairy tale writers have in turn used their tales as social and economic criticism, subversive works that for all their focus on the unreal, contain horror that is all too real.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, to find a book that uses a fairy tale to illustrate the horrors of the Holocaust. Or that the fairy tale fits that history so well.

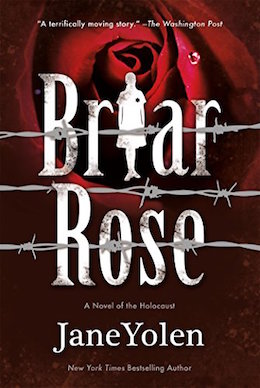

Jane Yolen, recently named an SFWA grandmaster, wrote Briar Rose as part of The Fairy Tale Series edited by Terri Windling, a series of novel-length fairy tale retellings intended for adults. For her retelling, Yolen chose the tale of Briar Rose/Sleeping Beauty, a dark story that in its earliest tellings focused on rape and cannibalism, and even in its somewhat sanitized retellings collected by the Grimm Brothers and artfully retold by Charles Perrault, still told of an entire castle filled with people put to sleep for one hundred years, caught up in something that they could not control.

Yolen’s retelling interweaves three stories: that of Becca Berlin, the sweetest, kindest and youngest of three sisters; Josef Potocki, a gay survivor of a German concentration camp inadvertently turned into a resistance fighter; and Briar Rose, in a version told and retold by Becca’s grandmother, Gemma. On her deathbed, Gemma claims to have been the princess in Briar Rose, and orders Becca to find the castle, the prince, and the maker of the spells.

This would seem to be the start of a fairy story, and indeed, Becca’s story is in many ways the closest that Briar Rose comes to the popular notion of a fairy tale, with a quest, a journey, and a man who might not technically be a prince (in the legal sense of that term) but might be able to help her wake up with a kiss. Becca’s role as the youngest of three sisters also reflects her traditional fairy tale role: her two older sisters, while fond of her, are also quarrelsome and unable to help her much on her quest. A few steps of her quest seem almost too easy, almost too magical—even if rooted in reality, lacking any real magic at all. But the rest of the novel is fiercely grounded in history and horror, even the retelling of Briar Rose.

Gemma’s version of Briar Rose contains some of the familiar fairy tale elements—the sleeping princess woken by a kiss, the wall of roses that shields the castle—but, as the characters realize, her version is far more horrific than the currently best known version of the tale, so horrific that as much as they love the story, her two oldest granddaughters protest hearing parts of it during Halloween. In Gemma’s version, not only are the briars and thorns lined with the skulls and ghosts of the dead princes, but no one other than Briar Rose and her daughter wake up. The rest are left in the castle. No wonder Becca’s friend claims that Gemma has it wrong, and her sisters often quarrel before the story ends, preventing them from hearing all of it. The real wonder is why Gemma feels the need to keep retelling the story, over and over: yes, her granddaughters love the story, but her obsession seems to be masking far more.

But the true horror is that of Josef, the Holocaust survivor, who begins as a casual intellectual and artist, fascinated by the theatre, ignoring—or choosing to overlook—the growing threat of the Nazis, and later finds himself watching the horrors at the Chelmno extermination camp. Though, in Yolen’s retelling, even his story has a hint of fairy tale: as she notes at the end of the novel, “happy ever after” is fiction, not history, and his story never happened.

The idea of merging the tale of Briar Rose/Sleeping Beauty with the horrors of the Holocaust might seem wrong, or impossible, but as it turns out, the tale does work, almost too well, as an illustration of Chelmno and its horrors. Yolen draws the comparisons methodically, inexorably, through Gemma’s retelling of the tale and Josef’s telling of his life: the parties (with ice cream!) that assured everyone that all was well, allowing them to ignore the growing evil; the barbs on the briars around the castle and the walls around the concentration camps; the way those outside the castle and the camps did not and perhaps could not look in; the way everyone inside the castle and inside the gas chambers fall over at once. The way even in the moments of greatest horror, birdsong and music can still exist.

Briar Rose was nominated for the Nebula Award and won the 1993 Mythopoeic Award. It is not a gentle read, or a fun read, but it is a beautiful novel, filled with quiet anger, and one I highly recommend—of only as an example of how fairy tales can be used both to reveal and heal trauma.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.